News

2nd Food for Justice International Workshop in Heidelberg

On July 22-24, 2024, the Second International Workshop “Food for Justice” took place at the Marsilius-Kolleg at Heidelberg University. The event was organized by Judith Müller and Renata Motta with the support of Alejandra Rojas (Junior Research Group Food for Justice at the Heidelberg Center for Ibero-American Studies, Heidelberg University), in cooperation with the Institute for Latin American Studies, Freie Universität Berlin and funded by the BMBF.

22 July 2024 – Exploring the field(s)

On the first day the workshop participants visited two places to engage with local food activists. First, a tour at the Markushof which works with the concept of Community Supported Agriculture. The group enjoyed a tour with the farmer and his family and a delicious lunch in their garden.

Second, the participants went to the HeidelBERG Café in the neighborhood Emmertsgrund in Heidelberg which hosts the innovative project “CookYourFuture”. After coffee and cake, the second activity of the day was a round table with activists from different NGOs, initiatives and projects around food based in Heidelberg an surroundings: Ernährungsrat Heidelberg, FIAN International, Über den Tellerrand, Tafel Heidelberg, CookYourFuture and Gemüserei Boden.Leben. The day ended with two presentations on FFJ Case Studies on CSA (Judith Müller) and Food Policy Councils (Lea Loretta Zentgraf) and a great dinner at the Heidelberg Café.

23rd and 24th of July: inputs, discussions and exchange around food

The second and third day explored the potential of food for socio-ecological transformations amidst multiple crises and inequalities. Highlights included discussions on agriculture’s socio-ecological impacts, food justice concepts, feminist and decolonial perspectives in food studies, the role of social movements in transforming food systems, and urban food policies and grassroots innovations.

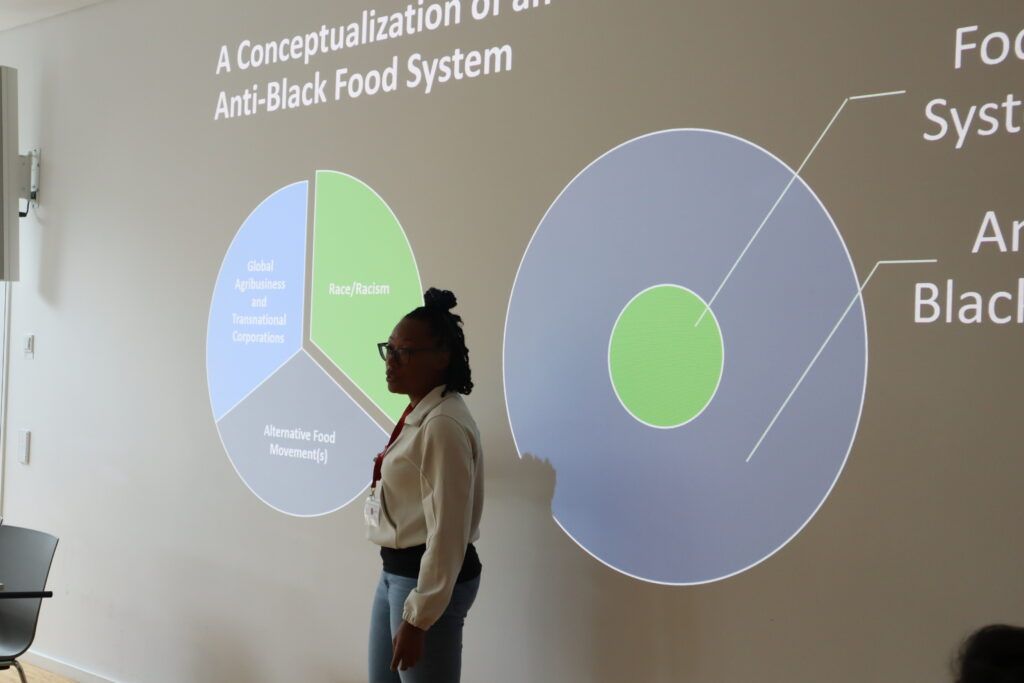

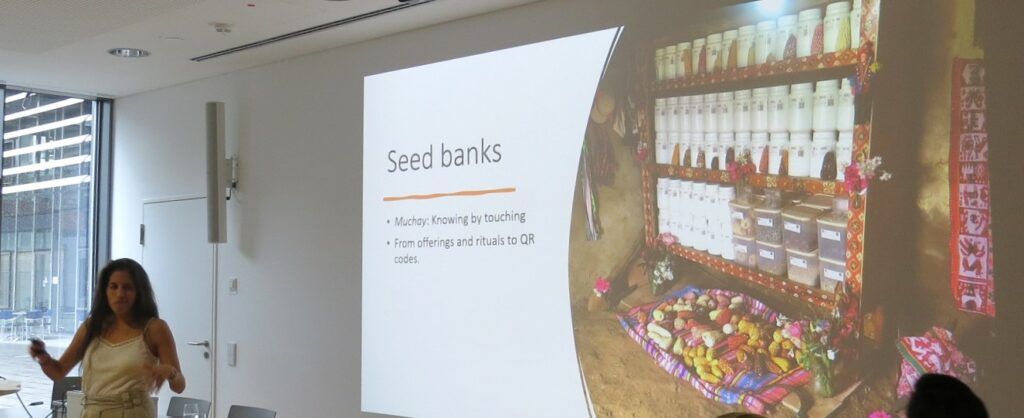

Presentations by Workshop Participants. July 23-24, 2024. Photos by Eryka Galindo and Lea Zentgraf.

Panel I: Transitions and Socio-Ecological Transformations in Food and Agriculture

The first panel, held on Tuesday, July 23rd, and moderated by Judith Müller (HCIAS, Heidelberg University) addressed the pressing socio-ecological crises driven by the intensification of agriculture. The session focused on the global increase in pesticide use, the homogenization of crops and livestock, and the transformation of food into financial assets, which contribute to issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and malnutrition. The panelists presented case studies from both the Global South and North, offering a global perspective on these challenges.

Firstly Sérgio Costa (FU Berlin, Germany) opened the panel by critiquing sociology’s anthropocentrism, highlighting its limitations in addressing the climate crisis. He argued for a post-anthropocentric sociology that recognizes the interdependence of all living beings and incorporates diverse knowledge sources, such as indigenous and activist perspectives, into a collaborative process between academics and non-academic actors.

Claudia Schmitt and Bruno Azevedo Prado (CPDA/UFRRJ, Brazil) examined the evolution of Brazil’s agroecological movement, which has challenged dominant agricultural practices since the 1970s. They analyzed how the movement navigates current crises, including climate change, threats to democracy, and green energy narratives, highlighting the tensions and changing dynamics within agroecology. Their research combined a literature review, document analysis, and interviews to explore these shifts.

Tomás Palmisano (University of Buenos Aires, Argentina) explored how Argentina’s alternative agriculture movement challenges the agribusiness model by restoring food’s value through local sovereignty, prioritizing domestic consumption, creating farmer-consumer networks, and using food as a political tool. He highlighted efforts to turn commodities into specialty products for niche markets.

Marco Antonio Teixeira (HCIAS, Heidelberg University) analyzed social movements in the Brazilian Amazon’s food system transformation amid the climate crisis. His research identified key actors, claims, and alternatives, emphasizing the importance of a holistic view that integrates food system struggles beyond the human-nature divide and highlighting the role of regional political actors in proposing alternatives.

The four speakers engaged in detailed discussions with workshop participants about their research on socio-ecological transformations.

Panel II: Food for Justice – Conceptual Debates, Everyday Practices and Political Implications

The second panel was held to explore the evolving concept of food justice, by tracing its roots in the environmental activism in the U.S. and addressing structural racism in food systems. Maria Trombini (HCIAS, Heidelberg University) moderated the discussion, emphasizing the importance of incorporating justice into socio-ecological transformations and highlighting the role of food in everyday practices of resilience and solidarity.

Ashanté Reese (University of Texas at Austin) discussed how Black gatherings, such as family reunions and cookouts, serve as vital spaces for nourishment and resistance against anti-Black violence. She argued that these gatherings offer essential lessons for strengthening food justice movements by emphasizing collective care and agency.

Meike Brückner (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) and Birgit Hoinle (Universität Hohenheim) introduced the concept of culinary justice, which examines the power dynamics embedded in culinary practices. They highlighted the need to address culinary inequalities and cultural oppression within food justice debates, urging a broader understanding that includes socio-cultural dimensions.

Desiree Lewis (University of the Western Cape) reflected on the limitations of focusing solely on material aspects of food justice, advocating for a more holistic approach that includes the poetic and affective dimensions of human freedom. She explored how food justice movements in South Africa generate new ways of understanding and practicing justice.

Thalita Kalix Garcia (Hertie School) analyzed the Slow Food movement in Brazil and Germany, examining how the concept of “good, clean, and fair food for all” varies across different cultural contexts. Her multi-sited ethnography revealed the diverse interpretations and actions within the movement, highlighting the challenges of achieving food justice in a multi-crisis world.

Panel III: Feminist, Intersectional and Decolonial Perspectives in Food Studies

The third panel moderated by Lea Loretta Zentgraf (HCIAS, Heidelberg University), explored the intersection of feminist and decolonial theories within food studies and politics. The discussion focused on the role of gendered political subjects in agriculture and food systems, emphasizing the importance of situating food movements in their specific social contexts to challenge colonial, patriarchal, and capitalist narratives. The panel highlighted contributions from diverse feminisms and examined the relationship between food sovereignty, ancestral knowledge, and agroecology across Europe and Latin America.

Rita Calvário (Universidade de Coimbra) presented research on migrant women farmworkers in Portugal and Spain, examining gender divisions in agricultural labor and their alignment with food sovereignty struggles. Her analysis of La Vía Campesina Europe’s documents provided insights into how these women navigate and challenge the gender politics within the food sovereignty framework.

Paola Solis Huertas (Gießen University) focused on Andean peasant women, challenging the essentialized views imposed by governments and development agencies. She introduced the concept of “Iskay Yachay,” highlighting how Andean women simultaneously manage different knowledge traditions. Her research showcased the importance of these embodied ways of knowing in fostering socio-ecological transformations in the Andes.

Mariana Calcagni (Freie Universität Berlin) analyzed the National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women (ANAMURI) in Chile, demonstrating how peasant movements mobilize political identities and material resources to drive socio-ecological transitions. Her study highlighted the role of rural women as key agents of social change, utilizing feminist political ecology and ecofeminism.

Renata Motta (HCIAS, Universität Heidelberg) discussed feminist coalitions in food politics, focusing on solidarity across rural-urban divides. She explored coalition-building in social movements such as Germany’s “Wir haben es satt!” and Brazil’s Marcha das Margaridas, emphasizing the importance of feminist politics in transforming food systems. Her work also examined the feminist food politics agenda in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, as an example of care-centered urban food policies.

Panel IV: Food Movements and Alternative Food Networks

On Wednesday 24th, the workshop opened with the fourth panel moderated by Juliane Dame (Universität Bonn), focused on global social movements striving for the transformation of food politics. The discussions highlighted how these movements intersect with broader struggles for agrarian reform, climate justice, and collective rights. Emphasizing the diverse scales of action, from local to global, the panel explored the roles of social movements, unions, and activists in shaping future agrarian and food systems through coalition-building, political agendas, and challenges faced in democratic participation.

Juliane Dame moderating the third panel. July 23, 2024. Photo by Carla Rossmann.

Paulo Niederle (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul) presented findings from a study initiated in 2020 on sustainable food systems in Rio Grande do Sul. In 2023, a dialogue platform involving 21 rural organizations was established to explore collective action for sustainable agriculture. Key challenges identified included the limited capacity of local organizations and public policies that exacerbated tensions over land use, making long-term political strategies difficult to implement.

Birgit Peuker (HCIAS, Heidelberg University) explored whether lifestyle politics (like growing one’s own food) and contentious politics (organized protests) conflict within German food movements. She concluded that they complement each other, with both personal practices and activism working together to challenge unsustainable food systems, emphasizing that effective organization is crucial.

Claudia Trinidad Giacomán Hernández (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile) explored vegan culinary activism in the Southern Cone, where meat consumption is deeply ingrained. Her research revealed that vegans in Santiago, Chile, use food as a non-confrontational tool to promote veganism. By sharing plant-based dishes and recipes, vegans engage in activism that normalizes veganism and encourages others to consider a plant-based diet as a viable option.

Eryka Galindo (HCIAS, Universität Heidelberg) examined the Brazilian Semi-Arid Articulation (ASA), a coalition advocating for coexistence with the semi-arid regions of Brazil. ASA’s approach, rooted in agroecology and the democratization of water and land access, aims to combat hunger and build fair, ecological food systems. The concept of “coexistence with the semi-arid” is central to their efforts, emphasizing the importance of water as a fundamental right and a key component in the fight against hunger in these vulnerable regions.

Panel V: Just Food Systems Transformation

The fifth panel moderated by Marco Antonio Teixeira (HCIAS, Heidelberg University), explored the complex relationship between urban food policies, state capacities, and grassroots innovations across different global contexts. This session highlighted how cities have become key players in addressing food security and justice, particularly in the wake of increasing urbanization and challenges posed by global crises like the Covid-19 pandemic.

Catia Grisa (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul) examined the role of municipal governments in shaping food policies in Brazilian cities. Her research focused on five capitals—Porto Alegre, Curitiba, Belo Horizonte, Salvador, and Manaus—revealing how the effectiveness of food policies is closely tied to the political and institutional capabilities of local governments. Factors such as the presence of dedicated bureaucratic structures, executive support, and the broader political-administrative environment were found to be crucial. The study highlighted the non-linear nature of food policy development, influenced by shifting societal configurations and power dynamics at various levels of government.

Lidia Cabral (Institute of Development Studies, UK) presented on grassroots innovations in food provisioning during the Covid-19 pandemic, comparing experiences across high- and middle-income countries (HMICs) like Brazil, Canada, France, South Africa, and the UK. She discussed how grassroots organizations responded to the crisis by experimenting with new food distribution methods, often in collaboration with volunteer networks and leveraging surplus food. These innovations opened up potential pathways for addressing systemic injustices in food systems, though sustaining these efforts post-pandemic poses significant challenges. The presentation emphasized the need for mutual learning across different contexts to enhance these transformative approaches.

Federico Masson (Freie Universität Berlin) focused on Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) in Germany, particularly the cooperative PlantAge e.G., as an example of how food movements challenge the dominant food system. Drawing on the concept of “food heterotopias,” inspired by Foucault, he described these cooperatives as counter-spaces that subvert conventional food production and consumption norms. By promoting solidarity, sustainable practices, and local food systems, these heterotopias contribute to the emergence of new social relations based on ethical principles, cooperation, and environmental stewardship.

Marit Rosol (Universität Würzburg) addressed the strategic dilemmas faced by food movements in their efforts to achieve broader social transformation. Her presentation drew on theories of social change, political economy, and intersectionality, discussing the challenges of tackling power imbalances and inequality within the food system. Based on discussions with Canadian food movement activists and researchers, she outlined potential strategies for overcoming these challenges to build more just and sustainable food futures.

The workshop concluded with a round table on global food justice challenges, fostering critical dialogues and connections to promote a democratic, ecological, and just food system.

The workshop’s food offerings were provided by various local initatives, each with a unique background and culinary focus. On the first day, participants gathered at the HeidelBERG Café, a community-driven hub in Heidelberg that fosters social integration through collaboration among various local institutions. The second day featured meals from Milinda Prabath Sievers‘ bright yellow food truck, offering a Sri Lankan menu with homemade spices, followed by classic Baden specialties served in the cozy, rustic setting of Gilberts Goldener Adler, a traditional restaurant in Heidelberg’s Handschuhsheim district. On the third day, fresh Turkish cuisine from Günay’s Garden, a combination of a greengrocer’s and salad bar, was provided, and the reception concluded with a taste of Spain from Paella Bros, who prepared authentic paella using traditional family recipes. Throughout the second and third days, participants also enjoyed sustainably sourced Venezuelan coffee provided by Daisy Schwartz and her family.